Strange clothes of sand

Labels: blogology

Labels: blogology

Labels: cheery thoughts, flummery, web 2.0

"This is going to be one of the great benefits of ambient/pervasive computing or everyware - not the tracking of objects but the tracking and collating of you yourself through objects."

This sentence works just as well with the word 'benefits' replaced by 'threats'. It all depends who gets to do the tracking and collating, I suppose.

If Slide is at all familiar, it's as a knockoff of Flickr, the photo-sharing site. Users upload photos, which are displayed on a running ticker or Slide Show, and subscribe to one another's feeds. But photos are just a way to get Slide users communicating, establishing relationships, Levchin explains.

The site is beginning to introduce new content into Slide Shows. It culls news feeds from around the Web and gathers real-time information from, say, eBay auctions or Match.com profiles. It drops all of this information onto user desktops and then watches to see how they react.

Suppose, for example, there's a user named YankeeDave who sees a Treo 750 scroll by in his Slide Show. He gives it a thumbs-up and forwards it to his buddy" we'll call him Smooth-P. Slide learns from this that both YankeeDave and Smooth-P have an interest in a smartphone and begins delivering competing prices. If YankeeDave buys the item, Slide displays headlines on Treo tips or photos of a leather case. If Smooth-P gives a thumbs-down, Slide gains another valuable piece of data. (Maybe Smooth-P is a BlackBerry guy.) Slide has also established a relationship between YankeeDave and Smooth-P and can begin comparing their ratings, traffic patterns, clicks and networks.

Based on all that information, Slide gains an understanding of people who share a taste for Treos, TAG Heuer watches and BMWs. Next, those users might see a Dyson vacuum, a pair of Forzieri wingtips or a single woman with a six-figure income living within a ten-mile radius. In fact, that's where Levchin thinks the first real opportunity lies - hooking up users with like-minded people. "I started out with this idea of finding shoes for my girlfriend and hotties on HotOrNot for me," Levchin says with a wry smile. "It's easy to shift from recommending shoes to humans."

If this all sounds vaguely creepy, Levchin is careful to say he's rolling out features slowly and will only go as far as his users will allow. But he sees what many others claim to see: Most consumers seem perfectly willing to trade preference data for insight. "What's fueling this is the desire for self-expression," he says.

I'm not sure that I see, in today's self-portraits on MySpace or YouTube or Flickr, or in the fetishistic collecting of virtual tokens of attention, the desire to mark one's place in a professional or social stratum. What they seem to express, more than anything, is a desire to turn oneself into a product, a commodity to be consumed. And since, as I wrote earlier, "self-commoditization is in the end indistinguishable from self-consumption," the new portraiture seems at its core narcissistic. The portraits are advertisements for a commoditized self

"And sin, young man, is when you treat people as things. Including yourself. That's what sin is. ... People as things, that's where it starts."

Labels: cheery thoughts, trends, web 2.0

Labels: drollery, e-business, flummery, predictions, trends, web 2.0

Larry Sanger, the controversial online encyclopedia's cofounder and leading apostate, announced yesterday, at a conference in Berlin, that he is spearheading the launch of a competitor to Wikipedia called The Citizendium. Sanger describes it as "an experimental new wiki project that combines public participation with gentle expert guidance."

The Citizendium will begin as a "fork" of Wikipedia, taking all of Wikipedia's current articles and then editing them under a new model that differs substantially from the model used by what Sanger calls the "arguably dysfunctional" Wikipedia community. "First," says Sanger, in explaining the primary differences, "the project will invite experts to serve as editors, who will be able to make content decisions in their areas of specialization, but otherwise working shoulder-to-shoulder with ordinary authors. Second, the project will require that contributors be logged in under their own real names, and work according to a community charter. Third, the project will halt and actually reverse some of the 'feature creep' that has developed in Wikipedia."

Of what value is publicly documenting the change history of an encyclopedia entry? How can something that purports to be authoritative allow the creation of alternative versions which readers can adopt as favorites?

If an attempt to craft a wiki that strives for accuracy, even via a flawed model, is considered something for “stick-in-the-muds”, then it’s apparent that many of Wikipedia’s supporters value the dynamics of its community more than the credibility of the product they deliver.

Larry Sanger famously suggested that Wikipedia must jettison its anti-elitism so that experts could feel more comfortable contributing. I think the real solution is the opposite: Wikipedians must jettison their elitism and welcome the newbie masses as genuine contributors to the project, as people to respect, not filter out.

I have begun to see what I think is a promising trend in the publishing world that may just transform the industry for good.

What I am suggesting is happening is the reversal of traditional publishing, i.e. the transformation of the system in which authors create and distribute their work. In the old system, it is assumed that the publishing process acts as a quality control filter ... but it ends up merely being a profit-capturing filter.

[...]

Conversely, in the new system, the works are made available, and it is up to the community-at-large to pass judgement on their quality. In the emerging system, authors create and distribute their work, and readers, individually and collectively, including fans as well as editors and peers, review, comment, rank, and tag, everything.

I’d love to add friends to my Flickr account, add my links to del.icio.us, browse digg for the latest big stories, customise the content of my Netvibes home page and build a MySpace page. But you know what? I don’t have time and you don’t either...

When everything (tag, username, number of people who have bookmarked an item) is a link, you can use any of those links to look around you. You can change direction at any moment.

the three needed data points in a folksonomy tool [are]: 1) the person tagging; 2) the object being tagged as its own entity; and 3) the tag being used on that object. Flattening the three layers in a tool in any way makes that tool far less valuable for finding information. But keeping the three data elements you can use two of the elements to find a third element, which has value. If you know the object (in del.icio.us it is the web page being tagged) and the tag you can find other individuals who use the same tag on that object, which may lead (if a little more investigation) to somebody who has the same interest and vocabulary as you do. That person can become a filter for items on which they use that tag.

If 'cloudiness' is a universal condition, del.icio.us and Flickr and tag clouds and so forth don't enable us to do anything new; what they are giving us is a live demonstration of how the social mind works.

A few days ago, Netscape turned its traditional portal home page into a knockoff of the popular geek news site Digg. Like Digg, Netscape is now a "news aggregator" that allows users to vote on which stories they think are interesting or important. The votes determine the stories' placement on the home page. Netscape's hope, it seems, is to bring Digg's hip Web 2.0 model of social media into the mainstream. There's just one problem. Normal people seem to think the entire concept is ludicrous.

while a lot of us geeks and 2.0 types are addicted to our own technology (and our own voices, to be honest), it's pretty darn obvious that A LOT of people want to stick with the status quo

our understanding of things changes and so do the terms we use to describe them. How do I solve that in this open system? Do I have to go back and change all my tags? What about other people’s tags? Do I have to keep in mind all the variations on tags that reflect people’s different understanding of the topics?

The social connected model implies that the connections are the important part, so that all you need is one tag, one key, to flow from place to place and discover all you need to know. But the only people who appear to have time to do that are folks like Clay Shirky. The rest of us need to have information sorted and organized since we actually have better things to do than re-digest it.

<...>

What tagging does is attempt to recreate the flow of discovery. That’s fine… but what taxonomy does is recreate the structure of knowledge that you’ve already discovered. Sometimes, I like flowing around and stumbling on things. And sometimes, that’s a real pita. More often than not, the tag approach involves lots of stumbling around and sidetracks.

<...>

It's like Family Feud [a.k.a. Family Fortunes - PJE]. You have to think not of what you might say to a question, you have to guess what the survey of US citizens might say in answer to a question. And that’s really a distraction if you are trying to just answer the damn question.

there's a demonstrative ritual often presented to incoming students at business schools. In one version of the ritual, a large jar of jellybeans is placed in the front of a classroom. Each student guesses how many beans there are. While the guesses vary widely, the average is usually accurate to an uncanny degree.

This is an example of the special kind of intelligence offered by a collective. It is that peculiar trait that has been celebrated as the "Wisdom of Crowds,"

<...>

The phenomenon is real, and immensely useful. But it is not infinitely useful. The collective can be stupid, too. Witness tulip crazes and stock bubbles. Hysteria over fictitious satanic cult child abductions. Y2K mania. The reason the collective can be valuable is precisely that its peaks of intelligence and stupidity are not the same as the ones usually displayed by individuals. Both kinds of intelligence are essential.

What makes a market work, for instance, is the marriage of collective and individual intelligence. A marketplace can't exist only on the basis of having prices determined by competition. It also needs entrepreneurs to come up with the products that are competing in the first place. In other words, clever individuals, the heroes of the marketplace, ask the questions which are answered by collective behavior. They put the jellybeans in the jar.

The balancing of influence between people and collectives is the heart of the design of democracies, scientific communities, and many other long-standing projects. There's a lot of experience out there to work with. A few of these old ideas provide interesting new ways to approach the question of how to best use the hive mind.

<...>

Scientific communities ... achieve quality through a cooperative process that includes checks and balances, and ultimately rests on a foundation of goodwill and "blind" elitism — blind in the sense that ideally anyone can gain entry, but only on the basis of a meritocracy. The tenure system and many other aspects of the academy are designed to support the idea that individual scholars matter, not just the process or the collective.

Wikipedia isn't great because it's like the Britannica. The Britannica is great at being authoritative, edited, expensive, and monolithic. Wikipedia is great at being free, brawling, universal, and instantaneous.

<...>

If you suffice yourself with the actual Wikipedia entries, they can be a little papery, sure. But that's like reading a mailing-list by examining nothing but the headers. Wikipedia entries are nothing but the emergent effect of all the angry thrashing going on below the surface. No, if you want to really navigate the truth via Wikipedia, you have to dig into those "history" and "discuss" pages hanging off of every entry. That's where the real action is, the tidily organized palimpsest of the flamewar that lurks beneath any definition of "truth." The Britannica tells you what dead white men agreed upon, Wikipedia tells you what live Internet users are fighting over.

The Britannica truth is an illusion, anyway. There's more than one approach to any issue, and being able to see multiple versions of them, organized with argument and counter-argument, will do a better job of equipping you to figure out which truth suits you best.

certain pages with a history of vandalism and other problems may be semi-protected on a pre-emptive, continuous basis.

How can communities support veterans going off topic together and newcomers seeking topical information and connections?

still qualifies as a 'lingering question'; I distinctly remember being involved in thrashing this one out, together with Clay, the best part of nine years ago. But this was the one that really caught my eye, if you'll pardon the expression:

What level of visual representation of the body is necessary to trigger mirror neurons?

Uh-oh. Sherry Turkle (subscription-only link):

a woman in a nursing home outside Boston is sad. Her son has broken off his relationship with her. Her nursing home is taking part in a study I am conducting on robotics for the elderly. I am recording the woman’s reactions as she sits with the robot Paro, a seal-like creature advertised as the first ‘therapeutic robot’ for its ostensibly positive effects on the ill, the elderly and the emotionally troubled. Paro is able to make eye contact by sensing the direction a human voice is coming from; it is sensitive to touch, and has ‘states of mind’ that are affected by how it is treated – for example, it can sense whether it is being stroked gently or more aggressively. In this session with Paro, the woman, depressed because of her son’s abandonment, comes to believe that the robot is depressed as well. She turns to Paro, strokes him and says: ‘Yes, you’re sad, aren’t you. It’s tough out there. Yes, it’s hard.’ And then she pets the robot once again, attempting to provide it with comfort. And in so doing, she tries to comfort herself.

What are we to make of this transaction? When I talk to others about it, their first associations are usually with their pets and the comfort they provide. I don’t know whether a pet could feel or smell or intuit some understanding of what it might mean to be with an old woman whose son has chosen not to see her anymore. But I do know that Paro understood nothing. The woman’s sense of being understood was based on the ability of computational objects like Paro – ‘relational artefacts’, I call them – to convince their users that they are in a relationship by pushing certain ‘Darwinian’ buttons (making eye contact, for example) that cause people to respond as though they were in relationship.

Recent Comments

viagra on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

hydrocodone cheap on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

viagra on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

alprazolam online on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

Timur on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

Timur on Sanger on Seigenthaler’s criticism of Wikipedia

Recent Trackbacks

roulette: roulette

jouer casino: jouer casino

casinos on line: casinos on line

roulette en ligne: roulette en ligne

jeux casino: jeux casino

casinos on line: casinos on line

What if dollars have no place in the new economics of content?

...

In media 1.0, brands paid for the attention that media companies gathered by offering people news and entertainment (e.g. TV) in exchange for their attention. In media 2.0, people are more likely to give their attention in exchange for OTHER PEOPLE’S ATTENTION. This is why MySpace can’t effectively monetize its 70 million users through advertising — people use MySpace not to GIVE their attention to something that is entertaining or informative (which could thus be sold to advertisers) but rather to GET attention from other users.

...

MySpace can’t sell attention to advertisers because the site itself HAS NONE. Nobody pays attention to MySpace — users pay attention to each other, and compete for each other’s attention — it’s as if the site itself doesn’t exist.

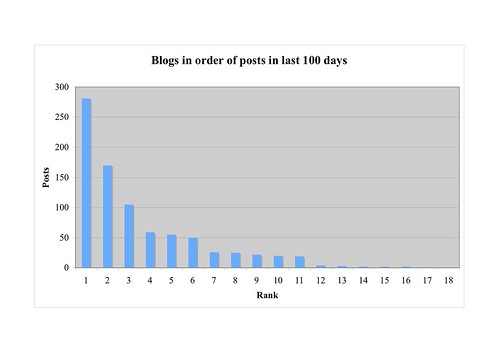

You see the same phenomenon in blogging — blogging is not a business in the traditional sense because most people do it for the attention, not because they believe there’s any financial reward. What if the economics of media in the 21st century begin to look like the economics of poetry in the 20th century? — Lots of people do it for their own personal gratification, but nobody makes any money from it.

"Most users are not trying to turn attention into anything else. They are seeking it for itself. For sure, the attention economy will not replace the financial economy. But it is more than just a subset of the financial economy we know and love."

I fear that to view the attention economy as "more than just a subset of the financial economy" is to misread it, to project on it a yearning for an escape (if only a temporary one) from the consumer culture. There's no such escape online. When we communicate to promote ourselves, to gain attention, all we are doing is turning ourselves into goods and our communications into advertising. We become salesmen of ourselves, hucksters of the "I." In peddling our interests, moreover, we also peddle the commodities that give those interests form: songs, videos, and other saleable products. And in tying our interests to our identities, we give marketers the information they need to control those interests and, in the end, those identities. Karp's wrong to say that MySpace is resistant to advertising. MySpace is nothing but advertising.

There's nothing rapid about this transition at all. It's been happening in the background for fifteen years. So let me rephrase it in ways that I understand. Shock revelation! A new set of technologies has started to displace older technologies and will continue to do so at a fairly slow rate over the next ten to thirty years!

...

My sense of these media organisations that use this argument of incredibly rapid technology change is that they're screaming that they're being pursued by a snail and yet they cannot get away! 'The snail! The snail!', they cry. 'How can we possibly escape!?'. The problem being that the snail's been moving closer for the last twenty years one way or another and they just weren't paying attention.

If one person is claiming that the world is moving fairly slowly, and has some sound advice on what this might look like (as you are doing here), and another person is claiming that the world is moving extraordinarily quickly, but offers some quickfire measures through which to cope with this, the sense of emergency will win purely because it is present. From here, it almost becomes *risky* not to then adopt the quickfire measures suggested by the second person. Panic becomes a safer strategy than calmness. Which explains management consultancy...

does web2.0 count as a snail too?

WSDL [Web Services Description Language] lets a provider describe a service in XML [Extensible Markup Language]. [...] to get a particular provider’s WSDL document, you must know where to find them. Enter another layer in the stack, Universal Description, Discovery, and Integration (UDDI), which is meant to aggregate WSDL documents. But UDDI does nothing more than register existing capabilities [...] there is no guarantee that an entity looking for a Web Service will be able to specify its needs clearly enough that its inquiry will match the descriptions in the UDDI database. Even the UDDI layer does not ensure that the two parties are in sync. Shared context has to come from somewhere, it can’t simply be defined into existence. [...] This attempt to define the problem at successively higher layers is doomed to fail because it’s turtles all the way up: there will always be another layer above whatever can be described, a layer which contains the ambiguity of two-party communication that can never be entirely defined away. No matter how carefully a language is described, the range of askable questions and offerable answers make it impossible to create an ontology that’s at once rich enough to express even a large subset of possible interests while also being restricted enough to ensure interoperability between any two arbitrary parties.

(Clay Shirky)

A Computational Grid performs the illusion of a single virtual computer, created and maintained dynamically in the absence of predetermined service agreements or centralised control. A Data Grid performs the illusion of a single virtual database. Hence, a Knowledge Grid should perform the illusion of a single virtual knowledge base to better enable computers and people to work in cooperation.

(Keith Cole et al)

variable A and variable B might both be tagged as indicating the sex of the respondent where sex of the respondent is a well defined concept in a separate classification. If Grid-hosted datasets were to be tagged according to an agreed classification of social science concepts this would make the identification of comparable resources extremely easy.

(Keith Cole et al)

work has been undertaken to assert the meaning of Web resources in a common data model (RDF) using consensually agreed ontologies expressed in a common language [...] Efforts have concentrated on the languages and software infrastructure needed for the metadata and ontologies, and these technologies are ready to be adopted.

(Carole Goble and David de Roure; emphasis added)

The service, called “Craigslist-GoogleMaps combo site” by its creator, Paul Rademacher, marries the innovative Google Maps interface with the classifieds of Craigslist to produce what is an amazing look into the properties available for rent or purchase in a given area. [...] This is the future….this is exactly the type of thing that the Semantic Web promised

(Joshua Porter)